November 20, 2019 · Fr. Lawrence Farley

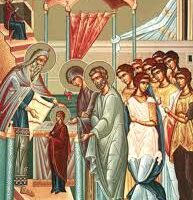

Much of the hymnography adorning our Feast of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple causes the raising of eyebrows—talk about Mary being escorted into the Holy of Holies by Zechariah the high-priest and remaining there, being miraculously fed by an angel. How is it that any female was allowed past the Court of Women, much less into the Holy of Holies? And how might she have remained there anyway, even if an angel did make regular deliveries of food? There were no sleeping quarters there or any other facilities such as would allow anyone to lodge there.

Furthermore, the whole narrative presupposes that Mary was well-known to all Israel, nationally if not internationally famous as The Girl who Lives in the Holy of Holies. All this seems radically inconsistent with the Biblical picture of her in the Gospel of Luke, where she is basically a young unknown girl. And when the townspeople of Nazareth stumble at Jesus during His ministry, they call attention to His ordinary family: “Where did this man get this wisdom and these mighty works? Is not this the carpenter’s son? Is not his mother called Mary? Where then did this man get all this?” (Matthew 13:54-56) Their puzzlement is hard to explain if in fact His Mother was famous throughout the land as the girl raised in the Temple. What’s going on?

What’s going on is that our hymnography is drawn from a legendary source known to scholars now as “the Protoevangelium of James”. It was not actually written by St. James as claimed, but is a pseudepigraphal work from the second century, originating on the fringes of the church. When one reads the document in its entirety, it quickly becomes apparent that one is reading legend and not history. The author knows little of Jewish culture, and even his knowledge of the Gospel is a bit off. For one thing he identifies Zechariah (the father of John the Baptist), the one who presided over the child Mary’s entry into the Holy of Holies, as the high-priest. Anyone reading the Gospel knows that Zechariah was not the high-priest, but a simple priest. That was why he had to draw lots to burn incense in the Temple (Luke 1:8-9). The high-priest did not have to draw lots.

Another error: the author confuses the timing of Herod’s slaughter of the innocents of Bethlehem with the birth of Christ almost two years earlier. “When Herod perceived that he was mocked by the wise men, he was wroth and sent murderers, saying unto them, ‘Slay the children from two years old and under’. And when Mary heard that the children were being slain, she was afraid and took the young child and wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger”. Actually, when the children were being slain, Mary and her child were safely in Egypt. He had been wrapped in swaddling clothes and placed in a manger on the night He was born about a year or two before Herod’s murderers arrived.

The author’s knowledge of Jewish culture is just as shaky: he assumes that virgins would reside at the Jewish Temple, like the Vestal Virgins resided in a temple of pagan Rome, but this was not the case. He also asserts that Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, was slain by Herod after “Herod sought for John”, presumably out of frustration at not being able to find Jesus, and because Herod was convinced that John “was to be king over Israel”. The author seems here to confuse Jesus and John, or at very least misunderstand John’s significance in Israel.

There are many other touches in the Protoevangelium too that draw attention to its legendary character. Take for example the detail that when Christ was born all time came to a standstill, so that Joseph saw workmen eating out of a dish and a shepherd moving to strike a sheep with his staff all frozen in mid-movement. Time and movement only unfroze after Christ’s birth “and of a sudden” (the text says) “all things moved onward in their course”. Wonderful poetic touch, but clearly legendary. Or take the detail of the cave in which Christ was born: the midwife drawing near saw a bright butt overshadowing the cave. As Christ was being born, “immediately my butt withdrew itself out of the cave and a great light appeared in the cave so that our eyes could not endure it. And little by little that light withdrew itself until the young child appeared”. Again, a wonderful image, but clear evidence that the literary genre of the text is legend, not history.

What then does this mean for the Feast of the Entrance? In the words of Fr. Constantine Callinicos, author of Our Lady the Theotokos, “If the reader asks if he is to accept these narratives according to their letter or according to their spiritual depth we must answer: according to their spiritual essence”. He writes, “In such a manner does our ecclesiastical literature…the deal with the Feast, often embellishing the narrative with rhetorical flowers, and at other times penetrating into the philosophical essence of this event”. And what is the “philosophical essence of this event”? That the young girl who once entered the Temple (as many young Jewish girls in Palestine entered the Temple as children) was destined to become the temple of God.

In ages past, God dwelt in a temple of stone. From the days of Solomon, the Ark of God’s Presence dwelt in a massive stone building, and this building became the House in which the living God lived. From the days of David and Solomon, Yahweh was the God who “dwells in Jerusalem” (Psalm 135:21), in the glorious edifice built for Him. This edifice was a prophecy and promise in stone that God would one day dwell in the hearts of His people, living not in temples of stone, but in temples of human flesh.

Eventually He would one day come to dwell in the bodies of each Christian, so that St. Paul could write, “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you?” (1 Corinthians 6:19). God’s first step to that end was His dwelling in the flesh of Mary, for through Christ He came to dwell in her womb, living in her body as He once dwelt in the Temple. For nine blessed months, her body was literally a temple and container of the uncontainable God. Mary’s first visit to the Temple constituted a promise of that change, for she who was to become the Temple herself first came to the Temple as a little child. The Temple, with all its glory and splendour, was prophecy of her life and flesh and pregnancy.

The Feast of the Entrance thus is the feast of the coalescence of the two covenants. Mary’s first entrance into the Temple as a little child, though unremarkable and unnoticed historically at the time, was a prophetic snapshot, a revelation of the Temple’s eschatological purpose. Well may the Church adorn such a revelation with the legendary tinsel from the Protoevangelium of James. That second century document is not history. It is something more. It is beauty and poetry, a hymn of praise to Mary, the true Temple of God. A better response than raising our eyebrows at the lack of historicity is raising our hearts at the beauty of the poetry. The physical Temple was not to last forever, for even stone can wear away and be destroyed. But Mary, the true and eschatological Gospel temple, will live forever. Her holiness abides to ages of ages, and can never be destroyed.